The Empress’s Crown: Lost in a Heist, Found in the Streets of Paris

In October 2025, one of the world’s most startling and dramatic cultural thefts unfolded at Musée du Louvre in Paris. While much of the coverage has naturally focused on the daring raid, the missing jewels and the investigation, here at NOTORIOUS Mag we turn our attention to something equally compelling: the object at the heart of the heist: the magnificent consort crown created for Eugénie de Montijo, Empress of the French, and the extraordinary artistry, history and symbolism that it carries.

A Crown for the Second Empire

While her husband, Napoléon III, never participated in a formal coronation, Eugénie de Montijo assumed the role of Empress with full imperial pageantry. In 1855, to coincide with the grand Exposition Universelle (1855) held in Paris, a crown was commissioned for her, a jewel not only of splendour but of political symbolism.

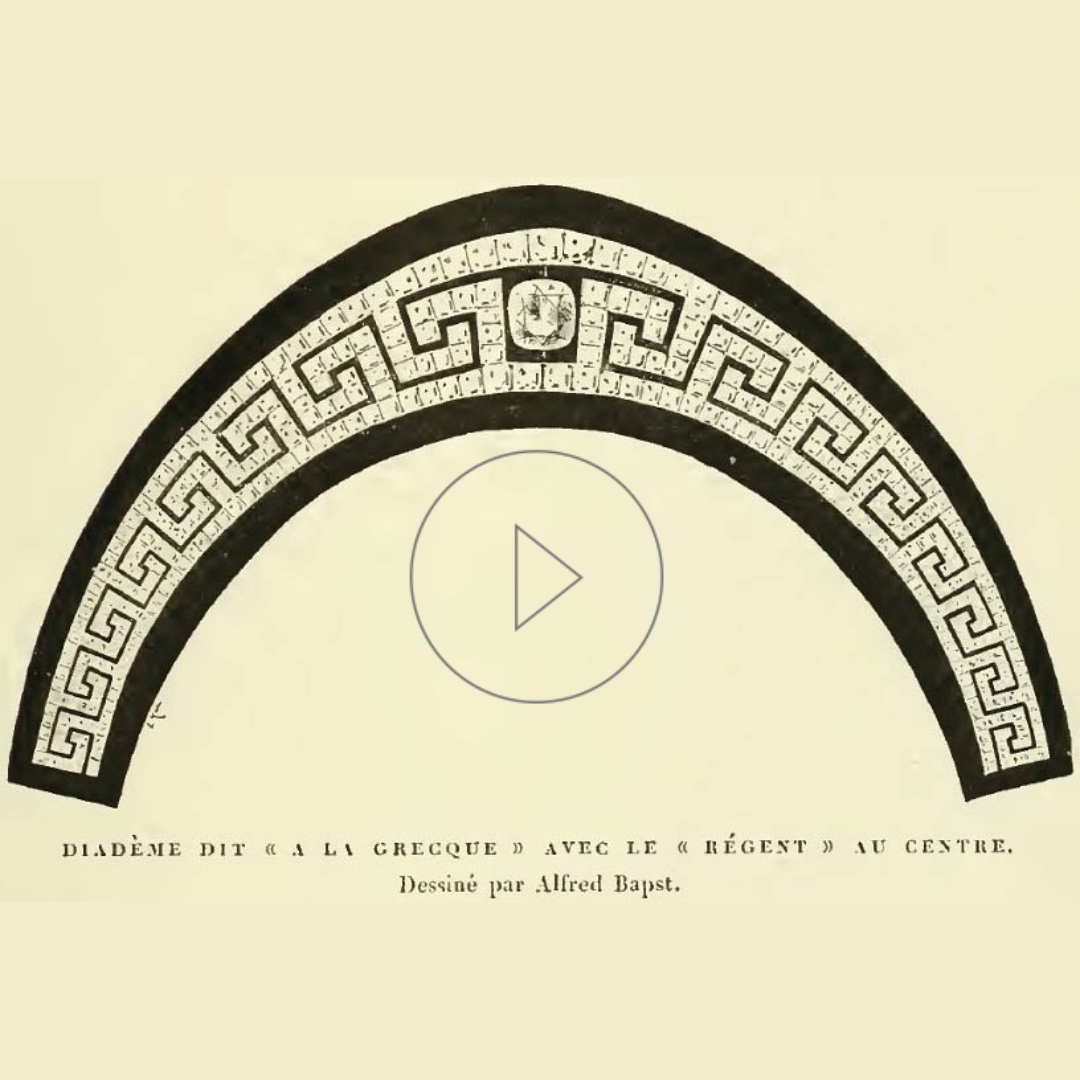

The design was entrusted to the talented jeweller Alexandre‑Gabriel Lemonnier (circa 1808-1884), who mounted hundreds of diamonds and emeralds. The structural execution and mounting were handled by the firm of jeweller J. P. Maheu. While intricate decorative components, notably the eagle motifs atop the arches, were crafted by the pair of gold-smith brothers August and Joseph Fannière.

At its core, this crown stands as a statement: the Second Empire resurrecting imperial grandeur, with the language of antique regalia, classical references and dazzling gemstones.

Technical Mastery and Materials

The crown is entirely made in gold, lavishly set with more than 1,300 diamonds (some sources say 1,354) and dozens of emeralds, one catalogue notes 56 emeralds in the piece.

The form: a traditional circlet of gold arches, crowned with a monde (the orb at the top) and finials in the shape of eagles, an explicit nod to the Napoleonic eagle and imperial symbolism. The eagles, cast and chased by the Fannière brothers, display the precision of gold-smith technique of the mid-19th century. The mounting of the numerous stones required not only aesthetic judgment but mechanical expertise, so that the gemstones would be securely set yet read lucidly from a distance when worn.

When viewed up close, one can observe the palmette and acanthus leaf scrolls in relief, the layering of gold filigree beneath the gem-settings, and delicate craftsmanship in the way the circlet supports the internal headband. It is not merely ornament; it is structural artistry.

Although the crown was never used in a formal coronation ceremony (Napoléon III abandoned formal coronation rituals), it served ceremonially, for state occasions, portraiture and representation. In this sense, the crown is less a “functional” coronation piece and more a wearable work of art, a symbol of power and prestige.

The Historical Significance

The crown occupies a special place in the broader story of the French Crown Jewels. Much of the regalia of the monarchy and empire was sold off by the Third Republic in 1887, yet certain pieces were retained or later returned. The Crown of Eugénie survived this dispersal, was eventually returned to her personally, then passed through inheritance, auction and donation, eventually entering the collections of the Louvre in 1988.

In the political and cultural context:

- The Second Empire sought to project continuity with France’s monarchical past while simultaneously asserting its new imperial identity. The eagle motifs, the palmettes, the diamonds, all reference classical and Napoleonic iconography.

- Empress Eugénie herself was a celebrated patron of fashion and jewellery; her taste helped define Parisian haute-joaillerie in the mid-19th century. The crown, therefore, is as much about personal style as it is about state ceremony.

- The use of large, high-quality stones and the scale of the piece reflect the wealth and ambition of the period.

Read: Prince Napoleon Bonaparte and a diamond theft The 40ct engagement ring

What the Crown Speaks to Today

Beyond its glitz and gem-count, the crown offers several layers of meaning that remain relevant:

- Craftsmanship at its apex — It is a benchmark of what skilled gold-smithing, gem-setting and design could achieve in 1850s France. For contemporary jewellers and historians of decorative arts, the piece serves as a reference point for technique, materials and visual vocabulary.

- Imperial iconography — The symbolism (eagles, monde, palmettes, arching circlet) reflect how jewellery can carry the weight of state identity and public image. The crown is wearable sculpture that articulates political authority.

- Cultural heritage and vulnerability — The fact that this crown was stolen (and later recovered damaged) from the Louvre brings into sharp relief how fragile our material links to history can be. The object is not just a jewel but a repository of memory and identity.

- Aesthetic endurance — Though it is over 170 years old, the design remains visually compelling. Modern viewers can still appreciate the interplay of light on diamonds, the rich green of the emeralds, and the subtle gold work. Its relevance is not constrained to its era.

In the Aftermath

When the crown was recovered (albeit damaged) after the heist, the fact that the piece had endured the vicissitudes of time only to be marred in modern times added a poignant twist. Its journey continues, from imperial commission, to museum display, to being part of a dramatic theft and recovery, yet its importance lies above all in its artistry and what it signifies.

For collectors, museum-goers and lovers of jewellery history, the Crown of Eugénie offers not simply sparkle but story. It invites admiration not only of its surface brilliance, but of the human hands, jewellers, gold-smiths, designers, who built it. It invites reflection on the ambition of an empire, the role of an empress, and the permanence (and impermanence) of objects that carry meaning.

As the dust settles on the heist headlines, our focus remains clear: this crown is a masterpiece of jewellery history, one whose value is immeasurable not only in carats but in craftsmanship, culture and legacy.

FAQ

| What is the Crown of Empress Eugénie? | The Crown of Empress Eugénie is a diamond and emerald tiara created in 1855 by Alexandre-Gabriel Lemonnier for Eugénie de Montijo, wife of Emperor Napoleon III. It represents the artistry and grandeur of France’s Second Empire. |

| Who made Empress Eugénie’s Crown? | Alexandre-Gabriel Lemonnier designed the crown with contributions from goldsmiths August and Joseph Fannière, who crafted the intricate eagle motifs symbolising Napoleonic power. |

| How many gemstones are in the Crown of Empress Eugénie? | The crown features approximately 1,354 diamonds and 56 emeralds set in gold, demonstrating the exceptional craftsmanship of 19th-century French jewellers. |

| Why was Empress Eugénie’s Crown stolen from the Louvre? | The crown was part of the French Crown Jewels on display at the Louvre and was stolen in a high-profile heist in 2025. It was later found damaged in the streets of Paris. |

| What is the historical significance of the Crown of Empress Eugénie? | It symbolises the rebirth of imperial France under Napoleon III, merging classical motifs with modern design, and stands as a masterpiece of 19th-century haute joaillerie. |

Images @Wikimedia Commons

SHARE